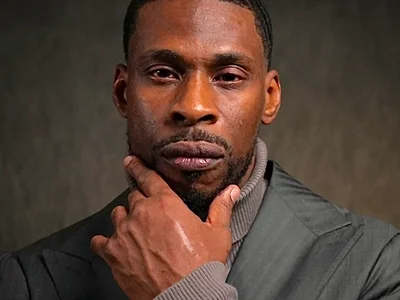

2024 Fellow

Growing up in St. Charles Parish, Louisiana, Tyler remembers his mother, Juanita Tyler, creating stylish dresses for herself and his sisters, from patterns sold in the JCPenney and Sears catalogs. His grandmother was a quilter, creating ornate designs from discarded clothes and newspapers. This familial knowledge of textiles was useful for Tyler, employing it to patch his clothes, and in his graphic quilt designs sold at the Angola Rodeo. Similarly, the ready-made has always had a place in Tyler’s oeuvre. In the mid-1970s, Tyler used readily accessible materials, including matchsticks and cigarette boxes, to create picture frames and jewelry boxes, calling to mind Henry Taylor’s early paintings and the shadow boxes of reclusive assemblage artist Joseph Cornell. Primarily working in textiles, Tyler learned to sew when he joined the Angola Prison Hospice Program, where participants created and sold elaborate handmade quilts to fund the program. Butterflies, flowers, and brightly-colored abstractions were common themes found in the applique patterned quilts he made in Angola. For Tyler, the image of the butterfly is symbolic of his life’s transformation, from being wrongly accused of murder at 16, to release from Angola 41 ½ years later. Although the butterfly remains a strong, recurring motif in Tyler’s work, this new body of applique quilts are created from photographs and images of his time incarcerated, many of which are on view in the vitrines that line the gallery walls. Hung from the walls at various depths, these works call to mind artist, traveler, and political activist Pacita Abad’s trapuntos, or high relief textile paintings. Although Tyler’s practice was not as peripatetic, he did learn to sew and quilt through relationships with others. For a time in the early 70s, Tyler lived with his sister in Los Angeles, California. The artist fondly remembers attending Watts Summer Festival at Will Rogers Park during the summer of 1970, and that the energy of self-expression at this moment in history was very self-actualizing. Just as his time in post-Watts Rebellion LA was extremely formative, returning to St. Charles Parish as a 14-year-old was a difficult shift. Tyler returned with an awareness of histories that were not being taught in school, and vocalizing this in classroom settings quickly earned him the label of troublemaker. Wrongfully accused of murdering a 13-year old boy during a conflict that occurred when a mob attacked a bus he was on during the height of school desegregation in St. Charles Parish, Louisiana, in 1974, Tyler would spend over four decades in Angola for a murder he did not commit.